Formation and Fragmentation

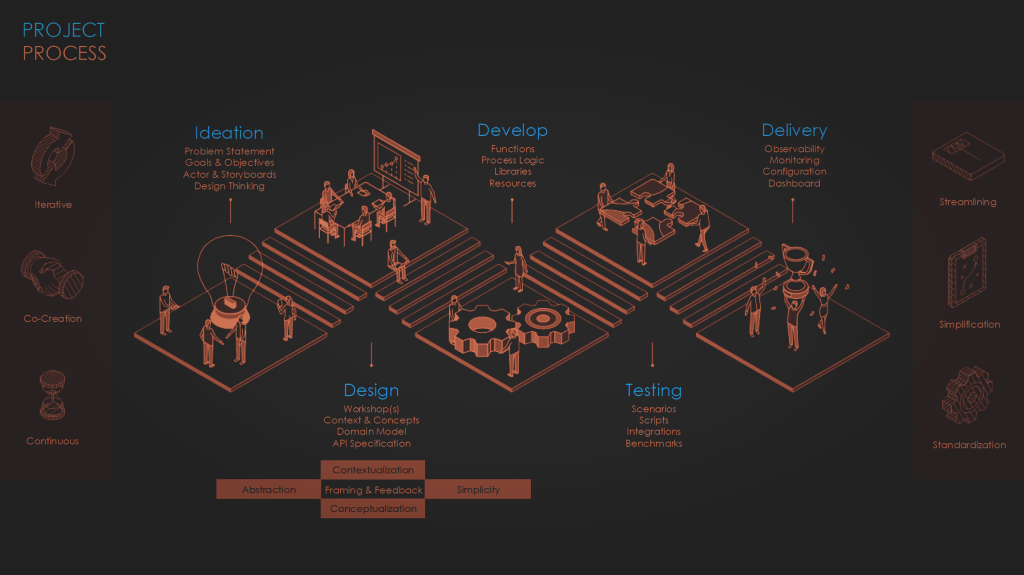

In complex systems, fragmentation into isolated units is an inevitable consequence when collaboration or coordination becomes too costly or uncertain. These units, commonly known as silos, function independently with minimal interaction beyond essential communication. This separation is particularly prevalent in engineering environments, where teams are granted significant autonomy, either intentionally or by default, without establishing a robust framework for aligning efforts and sharing resources.

As systems grow, they naturally drift towards disorder, characterized by increased entropy that deepens existing divides. Fragmentation, which occurs early in a system’s life, exacerbates this division, resulting in many disconnected pockets that function independently. The longer this segmentation persists, the more challenging and costly it becomes to reassemble these fragments into a unified and well-integrated system. This issue is particularly pronounced when organizations adopt Agile methods selectively, focusing primarily on delivering specific features rather than fostering holistic product development. This misuse of Agile, often driven by short-term goals, can speed up silo formation.

Alignment and Abstraction

Organizational silos extend beyond people and products; they also manifest in technical structures such as repositories, libraries, projects, and even the codebase itself. While breaking down a system into smaller parts can be a useful strategy for managing complexity, the crucial factor lies in the effectiveness of these connections and the organization’s ability to regularly reflect on the broader picture—the ecosystem.

Alignment goes beyond mere information exchange—it involves building bridges between different units, fostering shared work, and promoting reusable components. In contrast, abstraction is an ongoing process of identifying recurring patterns and developing adaptable solutions across diverse contexts. Both practices are essential for mitigating the drawbacks of isolation and enhancing overall efficiency.

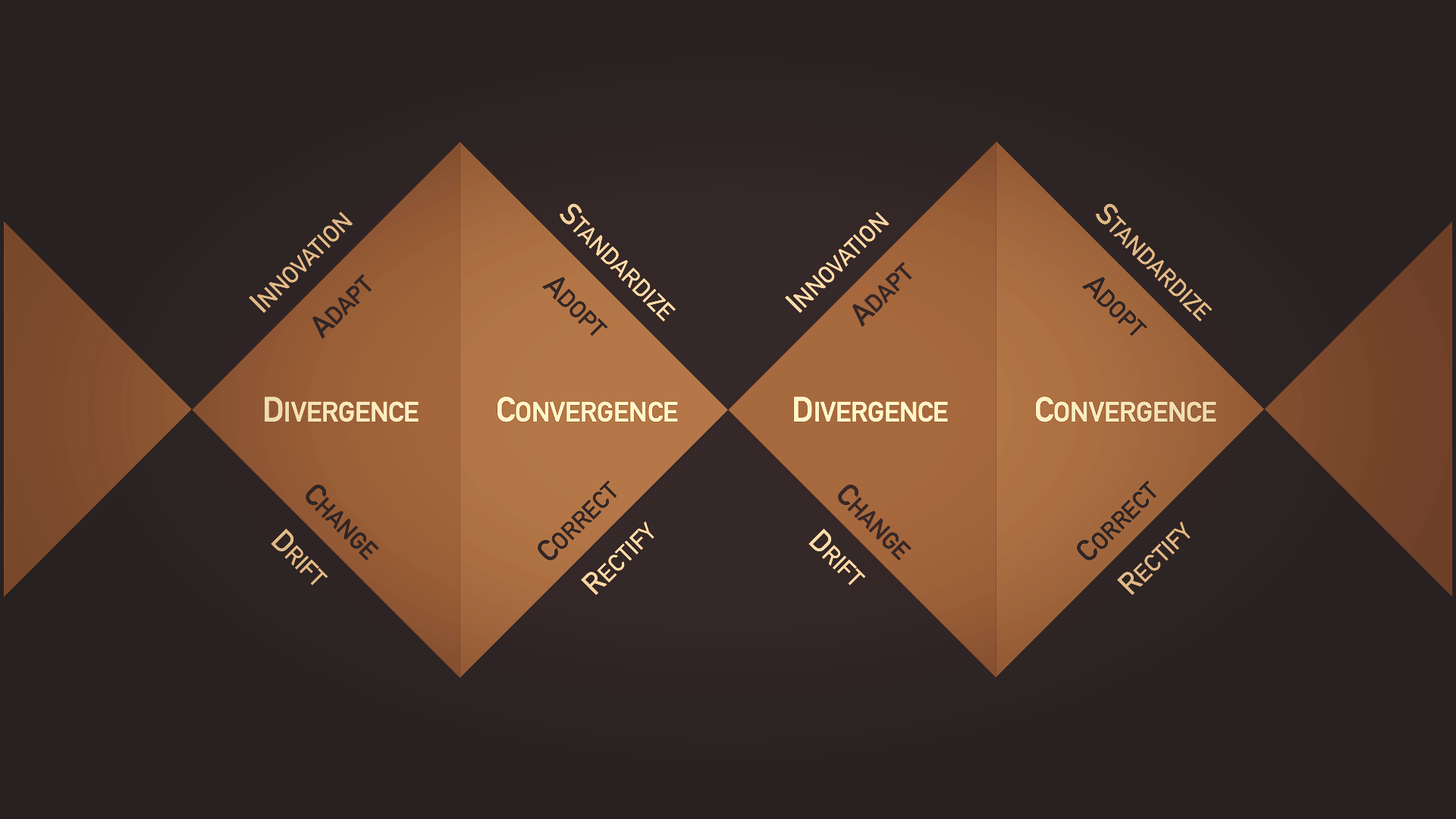

Divergence and Convergence

Diversity is crucial for innovation, enabling teams to explore diverse solutions. However, when different units diverge excessively in their focus, managing large-scale projects beyond silos becomes challenging.

While nurturing niche explorations is essential to seize opportunities, an organization’s effectiveness suffers when conflicting directions from misaligned subgroups constantly pull it apart.

Excessive compartmentalization can lead to inefficient resource utilization, missed opportunities for optimization, and reduced economies of scale. These inefficiencies hinder an organization’s ability to innovate and damage its competitive advantage. Moreover, the competition for resources among silos often results in territorial disputes, which hinder the exchange of ideas and limits diverse viewpoints.

While there is always a tendency for individual teams to diverge into their specific areas, it is crucial to keep this in check. Periodically, teams must come together to consolidate their findings and streamline processes. The art lies in maintaining a balance between diverging exploration and converging integration—allowing flexibility for innovation while ensuring the organization remains unified and efficient.

Communication and Culture

Silos frequently create barriers to open dialogue, leading to information hoarding and limited knowledge exchange within an organization. Consequently, duplicated efforts, missed collaboration opportunities, and incomplete solutions to broader challenges arise. Over time, these silos can foster a fragmented culture, where teams focus solely on their goals, often developing an “us versus them” mindset.

Such divisions significantly impact morale, diminish engagement, and fragment the organizational identity. Decision-making becomes challenging due to varying priorities among groups, leading to suboptimal choices. These divisions make long-term planning arduous, as teams pull in different directions, hindering their ability to converge on a shared vision.

Awareness and Adaptation

Managing silos demands consistent oversight and strategic approaches that consider both technical and human aspects. Early intervention is crucial to prevent divisions from solidifying, which would make future integration costly and risky. Organizations must strike a delicate balance between empowering teams to innovate and ensuring their alignment with overarching objectives. By adopting a comprehensive and forward-thinking approach, businesses can effectively mitigate the drawbacks of fragmentation.

By designing systems that promote sharing while simultaneously encouraging creativity, organizations can strike a delicate balance between flexibility and unity. This approach enables them to remain agile and adaptable in the face of complexity without compromising coherence or efficiency.

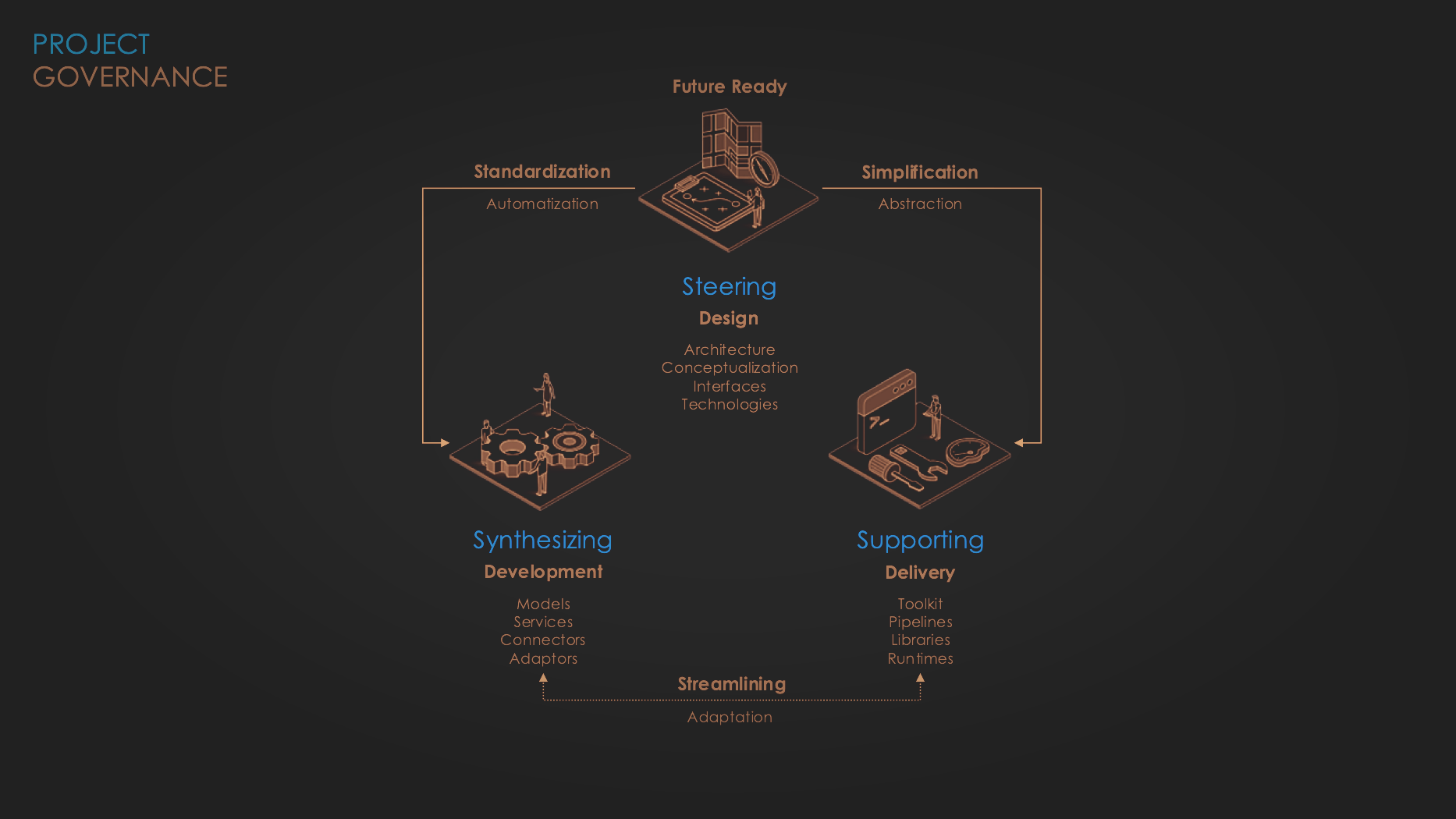

Standardization and Simplification

Organizations commonly prioritize two key initiatives, namely standardization and simplification, as they strive to evolve from a fragmented state to an integrated system or stack. Standardizing and simplifying serve as the North Star for Future Ready programs aimed at breaking down silos and fostering sharing. Standardization involves unifying processes, technologies, and frameworks within the organization to establish common practices, tools, and protocols; ensuring consistency and compatibility across systems. Through standards, organizations can better enforce governance, compliance, and security policies.

While standardization addresses silos, it can become rigid if overly prescriptive, potentially hindering creativity and innovation within teams that require flexibility. Simplicity ensures that standardization does not devolve into overly complex processes, platforms, and products. It guides initiatives aimed at reducing the cognitive load and operational complexity that frequently arise with large-scale enterprise systems.

Organizations often confuse standardization and simplicity because both can lead to efficiency gains. However, standardization does not always guarantee simplicity. A standardized process can still be intricate and challenging to understand or execute. Conversely, a straightforward solution may not be standardized and can vary based on the situation or user requirements. While standardization can simplify processes and enhance efficiency, it is not synonymous with simplicity. Organizations often assume that standardization, being easier to measure and implement, can be a shortcut to simplicity. However, true simplicity is not just about eliminating complexity; it is about meticulously designing and engineering with care and purpose. Achieving simplicity demands a deep understanding of users and the context, significant design effort, and effective change management. It requires patience and persistence.

Simplicity is not easy. It entails embracing uncertainty, experimenting, and staying committed to long-term goals despite short-term pressures. It is often an iterative, non-linear process that makes it difficult to track progress linearly or predict with certainty how long it will take to reach a simple solution.

Organizations must recognize the unique qualities of simplicity and standardization. They should appreciate the significant effort often required to achieve genuine simplicity. Only then can an organization approach a simplification initiative with greater realism in planning, resource allocation, and setting realistic expectations. Organizations that primarily focus on short-term metrics may struggle to justify or maintain a commitment to simplification projects that do not provide immediate, measurable benefits.

Abstraction and Automation

Simplicity and abstraction are two interconnected concepts that mutually reinforce each other in the design and development of intricate systems. Each concept catalyzes the refinement of the other, resulting in a more effective and efficient system as a whole. Simplifying a system facilitates the identification of its fundamental components and their relationships, leading to the creation of more effective abstractions.

By concentrating on the essential elements, designers can develop models that accurately capture the system’s behavior without being overwhelmed by extraneous details. Conversely, effective abstractions can lead to simpler systems. By representing complex concepts in a concise and comprehensible manner, abstractions enable designers to discern redundancies, inconsistencies, and unnecessary complexity. This process ultimately results in a simpler and more streamlined system design.

Likewise, standardization and automation are mutually reinforcing concepts that can substantially enhance the design, operation, and management of systems. By standardizing structural components and behavioral contracts, organizations can establish a more predictable environment conducive to automation. This, in turn, can lead to enhanced efficiency, diminished errors, and improved overall performance.

Change and Uncertainty

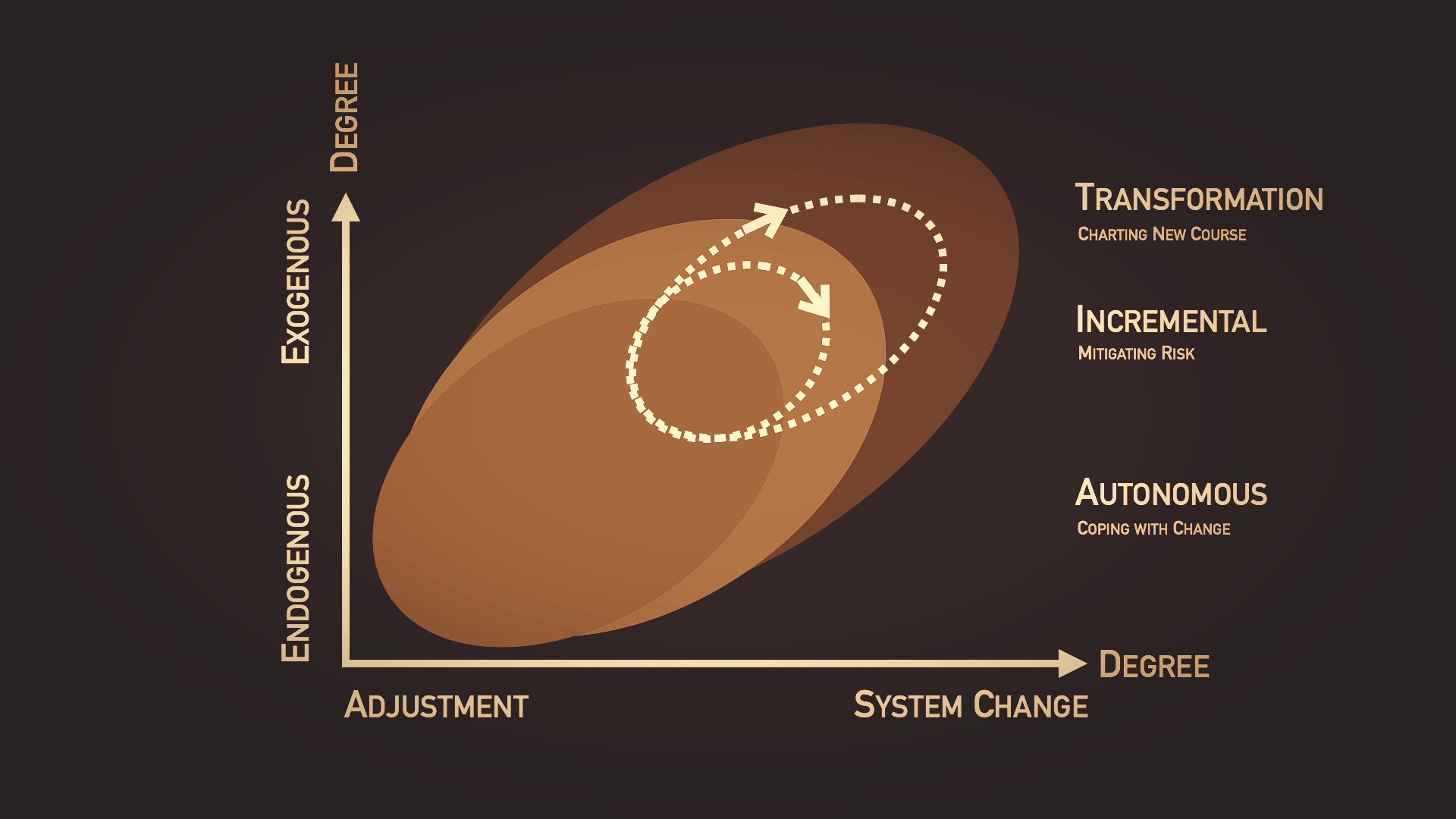

The pervasive uncertainty across industries has heightened the emphasis on measurable outcomes, resulting in a heightened fear of the unknown that often leads to an over-reliance on Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) and Objectives and Key Results (OKRs). This creates a cycle where teams are driven to produce outputs that can be measured and controlled in the short term, often at the expense of truly impactful work. While immediate feedback loops provide reassurance in times of uncertainty, they do not always capture the deeper, long-term value that transformational work can bring.

Organizations frequently resort to metrics that offer rapid validation in uncertain environments, despite the paradoxical nature of this approach, which invariably leads to superficial improvements that fail to address fundamental issues or generate long-term value. Consequently, the more intricate and nuanced work that could lead to considerable change is marginalized because it does not immediately align with indicators and outcomes. This risk-averse culture can hinder experimentation, exploration, and long-term thinking, essential for achieving simplicity, innovation, or significant improvements.

While uncertainty can compel us to prioritize measurable and controllable tasks, it is equally crucial to allocate space for high-value but less predictable work. This involves embracing uncertainty, valuing exploration and learning, communicating effectively, and cultivating a supportive work environment. We can effectively navigate uncertainty and achieve long-term success by adopting these strategies. True value lies in our ability to navigate uncertainty effectively, rather than in the illusion of control provided by short-term metrics. Balancing the need for immediate feedback with the pursuit of longer-term, transformative value is a key challenge for modern organizations.

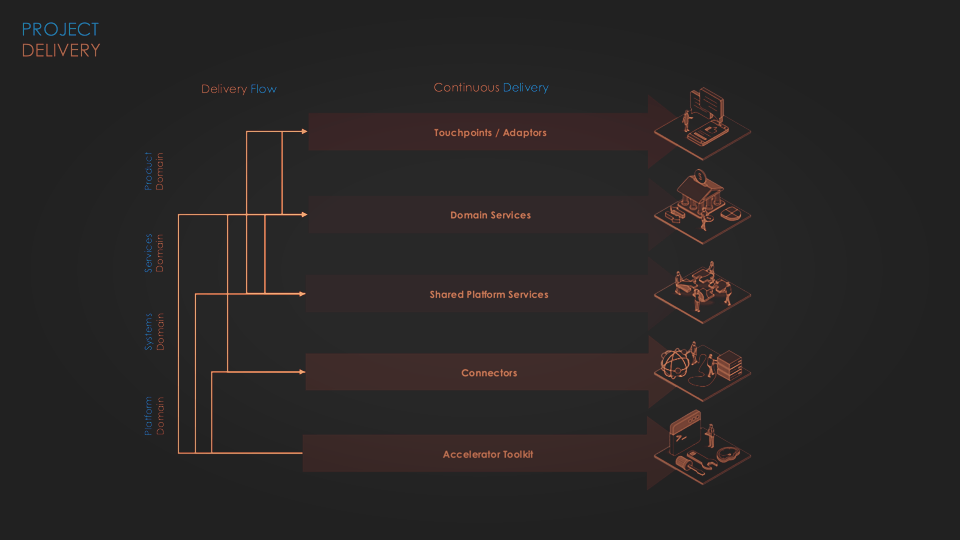

Transitioning and Transformation

Moving to a more standardized and simplified sociotechnical environment presents challenges. Individuals accustomed to their familiar tools and methods may resist the change. The initial transition can be costly and disruptive. Leaders must carefully strike a balance between the desire for uniformity and the occasional need for specialized solutions in specific areas. Engineers, in particular, tend to dislike change more than anything else, particularly the transition period between the old and the new.

Transitioning from fragmentation to integration is a gradual process that successful organizations embark on as a journey. Changes are implemented incrementally, accompanied by transparent communication with all stakeholders. Investing in training and support is essential to help employees adapt to the new standards and change mindsets from closed and isolated to open and collaborative. Regular evaluations are conducted to ensure that the selected standards remain relevant and efficient.

As the silos are dismantled, the organization experiences a surge in cohesion, productivity, and creativity. The streamlined technical infrastructure serves as a solid foundation for growth, enabling the enterprise to swiftly adapt to market fluctuations and technological advancements.

In this new integrated environment, the primary focus shifts from merely maintaining a disjointed status quo to stimulating innovation and enhancing value creation. Engineering teams, once operating independently, now seamlessly collaborate, leveraging shared resources and knowledge. Previously burdened by technical debts and silos, the organization is poised to assume a leadership role in the digital era, supported by a unified, adaptable, and effective technological framework.