We ask too much of people.

When complex systems fail—when the cascade begins, when latencies spike, when the orchestration collapses into chaos—we expect human operators to make sense of it. We hand them logs. Millions of lines, timestamped to the millisecond, each one true, and each one is useless in isolation. We hand them metrics. Dashboards of time-series data, red lines crossing thresholds, alerts firing in clusters that obscure rather than illuminate. We hand them traces. Graphs of request flows that capture what happened but can’t explain why.

And then, when they can’t synthesize this deluge into understanding fast enough—when the system continues to degrade while they search for causation amid correlation—we ask what went wrong. We write a post-mortem. We identify “root causes.” We assign blame, sometimes explicitly, more often through implication: someone should have seen it coming.

But no one could have seen it coming. Not because the operators lacked skill or vigilance, but because we never gave them the means to perceive the system as it actually exists. We gave them artifacts instead of awareness, archaeology instead of experience, forensics instead of foresight. We built an entire industry—observability, we call it—around the premise that if we collect enough data about what systems do, understanding will somehow emerge.

It doesn’t. It can’t. And the people caught in the gap between data abundance and genuine comprehension pay the price in stress, in blame, in the quiet erosion of their sense of competence when facing systems that have grown beyond human cognitive capacity to grasp.

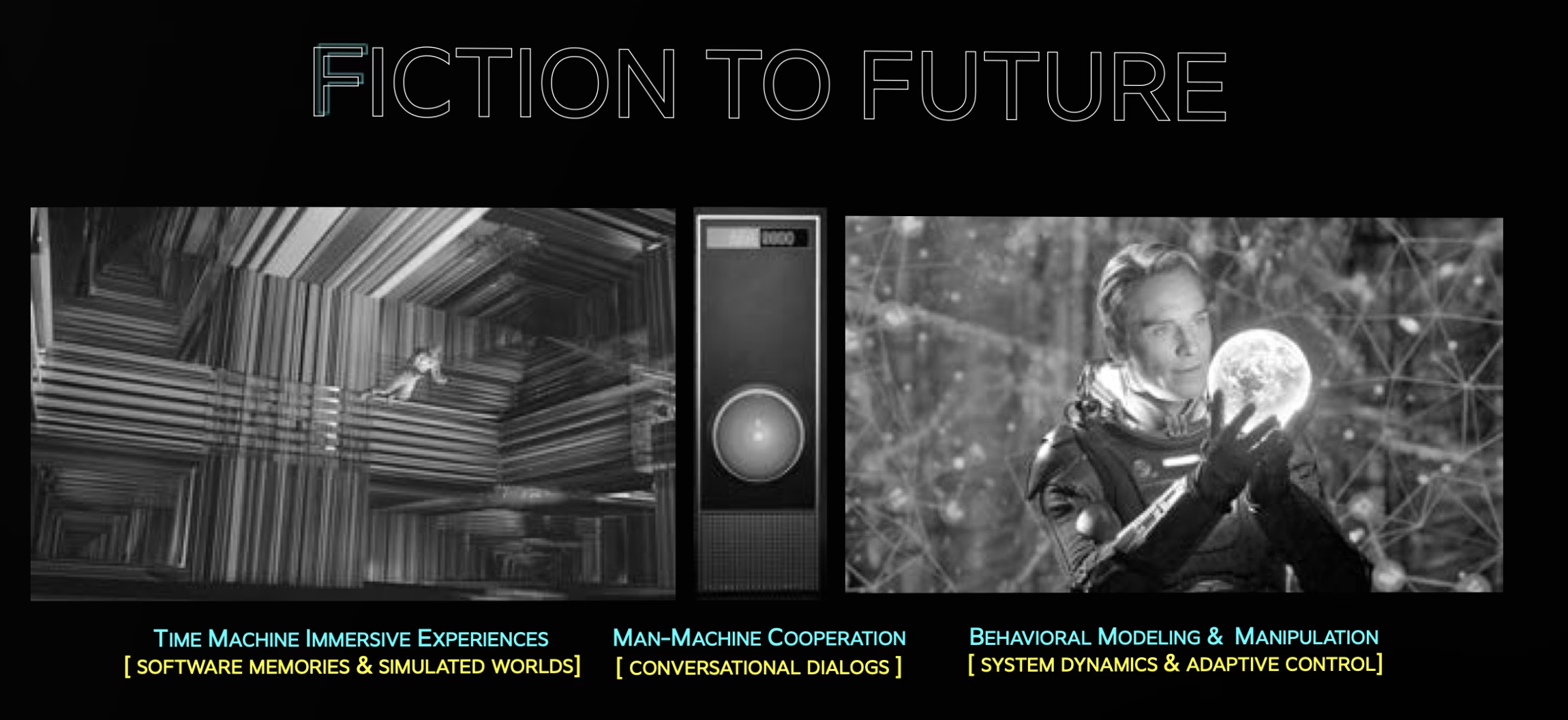

This essay is about a different path—one that was signposted a decade ago and remains largely untaken. It concerns three capabilities that genuine operational intelligence requires, capabilities that current approaches to AI in operations don’t provide and, more importantly, can’t provide without a fundamental architectural change. These aren’t product features or roadmap items. They’re prerequisites for what we claim to want: machines that can truly perceive, reason about, and act upon the living dynamics of complex systems. Machines that can partner with humans rather than simply serving them faster queries.

The three pillars are: the capacity to move through system states in time, simulating past and future; conversational interfaces that translate between mechanical observation and human situation; and behavioral models that enable not just pattern recognition but genuine understanding of system dynamics. Together, they form the architecture of what agentic AI in operations would actually mean. Separately, each illuminates why current approaches—no matter how sophisticated their pattern matching—remain fundamentally incomplete.

The Time Machine

The first pillar seems almost prosaic when stated simply: systems should be able to move through their own history and project into possible futures. But the implications run deep, and what we currently call “historical analysis” barely scratches the surface of what this means.

Consider what observability platforms offer today. You can query logs from a specific time window. You can display metrics for the last hour. You can inspect a distributed trace to see how a request flowed through services. This feels like examining the past, and in a narrow sense, it is. But it’s artifact archaeology, not time travel. You’re reading ancient texts, not experiencing the world as it was.

The difference is fundamental. Historical log queries answer the question: what messages did we capture? They can’t answer the more essential question: what was the system doing? Because a system’s behavior emerges not from individual events but from flows, pressures, coordination patterns, and topological configurations—dynamics that exist between and across the artifacts we happen to record.

Imagine debugging a cascade failure with the tools we have. The logs tell you that Service A began throwing errors at 14:03. They tell you that Service B experienced timeouts at 14:04. They tell you that Service C restarted at 14:05. Each fact is accurate. The sequence is clear. And yet you can’t see the actual causation because the logs capture symptoms rather than dynamics.

What you can’t see: that Service A’s output flow doubled without Service B’s intake capacity increasing proportionally. That pressure accumulated at the boundary between them for eight minutes before manifesting as the timeouts you eventually observed. That Service C’s restart was an adaptive response to backlog saturation, not a failure. The true origin was a topology change thirty minutes earlier that created a new flow path bypassing rate limiting. The logs are true, but the story they tell is incomplete in precisely the ways that matter for understanding.

A time machine for systems would allow reconstruction of the system state at any point—not just the events that were logged, but the structure that existed, the flows that circulated, the stability conditions of each boundary. It’d allow simulation forward from any state, revealing trajectories: if this inlet rate continues, when does saturation occur? It’d allow counterfactual exploration: what happens if we scaled earlier, or throttled differently, or rerouted this flow?

This transforms debugging from forensic analysis into experiential understanding. Instead of reading about what happened—constructing narrative from fragments, inferring causation from correlation—you could inhabit the system state as it unfolded. You could perceive the pressure building, feel the flows diverging, and anticipate the cascade before it arrives.

For this to work, systems must maintain memories richer than logs.

Topological memories: how was the system structured, what fed what?

Flow memories: what circulated, at what rates, with what characteristics?

Stability memories: what were the qualitative states of each subsystem boundary?

Pattern memories: what constituted normal for this context, this time of day, this workload profile?

These aren’t event records but state histories—snapshots of dynamic configuration that can be reconstructed and navigated. The implications for AI agents are profound.

A diagnostic agent with time machine capability doesn’t correlate events to guess at causation. It inhabits past system states to perceive the dynamics that led to failure.

A predictive agent doesn’t extrapolate trends from metrics. It simulates forward from the current state to anticipate where pressure will accumulate, which boundaries will saturate, and which flows will cascade.

An optimization agent doesn’t guess at configurations. It explores counterfactual scenarios, testing changes in simulation before applying them to the living system.

This is an AI that reasons about systems temporally rather than statistically. Without time machine capability, agents are trapped in a past moment, analyzing events without the context of trajectory or alternative futures. With it, they can think as experienced operators think: we’ve been here before; I recognize this pattern; I know how this unfolds; here’s what happens next.

The Conversation

The second pillar addresses what might seem like a solved problem: how do machines and humans communicate about system state? We have natural language interfaces now. We can ask our observability tools why latency spiked, and they’ll summarize logs and correlations in plain English. Is this not a conversation?

It isn’t. It’s natural language access to databases. The conversation is about artifacts—about what was recorded—rather than about the system itself. The distinction matters because it determines whether AI becomes a genuine partner in operations or merely a more articulate query interface.

When an operator asks what’s happening with warehouse orchestration, what do they need? Not a summary of recent error messages. Not a correlation of metric spikes. They need situational awareness: the warehouse orchestration boundary is diverging; input doubled eleven minutes ago without a proportional increase in routing output; pressure is accumulating and will reach the critical threshold in approximately eight minutes at the current rate; this pattern is novel, not seen in the past thirty days. This response describes dynamics, not data.

- Flow imbalance: input exceeds output.

- Pressure accumulation: the consequence of that imbalance.

- Trajectory: time to saturation.

- Novelty: comparison against baseline patterns.

- Boundary identification: which subsystem is affected?

The conversation is about the organism’s vital signs rather than its medical records.

The translation challenge here isn’t merely linguistic but ontological. Machines perceive data streams with rates and latencies, port utilization percentages, and graph topologies with edge weights. Humans think in qualitatively different terms: pressure is building; that subsystem is saturated; flows are backing up; the coordination is breaking down. Bridging this gap requires translation not just between languages but between levels of abstraction—from quantitative observations to qualitative situations, from measurements to meanings.

Genuine situational awareness has specific characteristics. It’s contextual, understanding what matters now for this particular situation. It’s anticipatory, recognising trajectories rather than just current states. It’s hierarchical, capable of zooming from system-wide overview to subsystem-specific detail as needed. It’s actionable, surfacing what matters for decisions rather than comprehensive data dumps.

Current AI observability fails these tests. Ask it what’s wrong, and it returns lists of error messages, correlations across metrics, affected services, and timestamps. But an operator making decisions needs different information: where is the problem, which boundary is affected? What kind of problem is it—flow imbalance, coordination failure, or resource exhaustion? How urgent is it—what’s the trajectory toward failure? What should be done—which inlet to throttle, which outlet to expand, which coordinator to invoke?

Beyond individual exchanges, genuine cooperation requires multiple conversational modes.

- Diagnostic dialogue, where the human asks the AI to narrate the state transitions that led to the current situation.

- Exploratory dialogue, where a human asks what happens if capacity increases, and the AI simulates the counterfactual.

- Monitoring dialogue, where the AI alerts to divergence and the human provides context that shapes the response.

- Coordination dialogue, where the AI recommends interventions with calculated tradeoffs and the human decides.

- Learning dialogue, where the human explains that a particular pattern is expected, and the AI updates its baseline model.

Each mode serves different operational needs. Together, they enable partnership rather than query-response.

There’s also a social dimension rarely considered. Man-machine cooperation isn’t one human talking to one AI. It requires social intelligence about who needs to know what, and when. Which team members have context on this subsystem? Who should be notified about this divergence? What’s the escalation path if this boundary fails? Who made the recent topology change that’s relevant here? AI that only answers questions when asked, without understanding operational context—team structures, on-call rotations, domain expertise, decision authority — doesn’t coordinate responses effectively.

For agentic systems, conversational capability is ultimately about shared understanding. It enables negotiation of control boundaries between humans and machines. It enables the explanation of autonomous actions in terms that humans can evaluate. It enables collaborative diagnosis where human domain knowledge meets machine perceptual capability. It enables trust-building through transparency about confidence, reasoning, and limitations.

Cooperation requires more than command execution. It requires shared mental models and mutual understanding of the system state. Without this, we’d have sophisticated tools. With it, we have partners.

The Model

The third pillar may be the most fundamental: to understand systems, you must model them; to control systems intelligently, you must model their behavior. This is where current AI observability reveals its deepest limitation. Pattern matching on artifacts isn’t behavior modeling. Correlation analysis isn’t system dynamics. You can’t manipulate what you don’t model.

Current approaches apply machine learning to telemetry with increasing sophistication. Anomaly detection identifies unusual metric patterns. Clustering groups of similar error messages. Correlation analysis links spans across distributed traces. These techniques find patterns, and finding patterns is useful. But patterns aren’t models.

A pattern tells you that when metric X spikes, metric Y usually spikes thirty seconds later. A model tells you why: Subsystem A feeds Subsystem B through a bounded queue; when A’s output exceeds B’s processing capacity, pressure accumulates in the queue; after saturation, A experiences backpressure manifesting as increased latency in A’s input processing. The pattern describes co-occurrence. The model explains the mechanism.

This distinction matters enormously for control. Consider an AI agent trying to prevent an incident. With patterns alone, it sees the error rate increasing, correlates this with a recent deployment, and recommends a rollback. This is reactive control based on historical correlation—reasonable but shallow.

With a behavioral model, the same agent perceives that the input flow to Subsystem A has doubled. It models forward: A’s output feeds a bounded inlet at Subsystem B. It projects: B will saturate in eight minutes at the current rate. It calculates interventions: throttle A’s inlet by a specific percentage, or scale B’s capacity by a specific amount, or provision additional B replicas. This is anticipatory control based on dynamic understanding—acting on predicted future states rather than reacting to current symptoms.

The difference between seeing patterns and understanding behavior is the difference between reacting to symptoms and controlling dynamics.

System dynamics, the discipline that emerged from Jay Forrester’s work at MIT, provides a framework for this kind of modeling. Stocks represent accumulated quantities—queue depths, connection pool sizes, pending requests. Flows represent rates of change—request rates, processing throughput, and error generation.

Feedback loops capture how flows affect stocks, which in turn affect flows. Applied to distributed systems, services have input and output flows, internal queues and buffers are stocks, processing capacity governs flow rates, backpressure creates negative feedback, and retry logic can create positive feedback that amplifies failures.

This gives you behavioral equations rather than statistical correlations. Queue depth at the next time step equals the current queue depth plus inlet flow minus outlet flow. If the queue depth exceeds the capacity, apply backpressure to the inlet, signal degradation in the status. With these models, you can predict when saturation occurs, calculate required capacity for target latency, understand why retry storms amplify failures, and design coordination protocols that maintain stability.

The holonic perspective extends this framework with a nested structure. Each holon—each whole that’s also a part—has inlet and outlet ports. Internal processing transforms inlet flows to outlet flows. Processing capacity and buffering are stock variables. Flow characteristics are observable dynamics. A holon’s internal structure is itself a network of sub-holons. Flow dynamics at one level emerge from dynamics at lower levels. Control can be applied at any level of the hierarchy.

This leads to stability classification as a first-class concept. A boundary can be converging, with flows returning to baseline. It can be stable, with flows within normal bounds. It can be diverging, with flows moving away from the baseline —the early warning of potential failure. It can be erratic, oscillating unpredictably. It can be degraded, operating at reduced capacity but still functional. It can be down.

These classifications aren’t descriptions but computations. You can simulate a holon’s response to input patterns. You can predict when state transitions occur—from stable to diverging to degraded. You can calculate intervention points. You can optimize flow routing across alternative paths.

Behavioral models enable what cybernetics calls adaptive control—the ability to adjust system behavior dynamically based on perceived state. Feedback control monitors outlet flow against the target rate and adjusts inlet throttling to maintain balance. Feedforward control detects incoming flow surge and preemptively scales outlet capacity before queue saturation. Cascade prevention detects a diverging boundary in one subsystem, models downstream dependencies, and preemptively isolates or throttles to prevent propagation. Topology adaptation detects bottlenecks, provisions alternative routing, and dynamically reconfigures flow paths to maintain throughput.

This operates at multiple levels simultaneously. Individual holons self-regulate, monitoring their own inlet-outlet balance, applying backpressure when approaching saturation, signaling status to coordinators.

Coordinator holons manage groups, balancing flows across parallel components, rerouting around degraded subsystems, and provisioning additional capacity. Global optimizers manage topology, analyzing overall circulation patterns, identifying structural bottlenecks, recommending, or executing topology changes.

Meta-control shapes policy, defining target stability levels, setting capacity provisioning rules, and establishing intervention thresholds.

With behavioral models and adaptive control, AI agents move beyond assistance to genuine operational intelligence. Diagnostic agents don’t just find correlations but explain mechanisms. Predictive agents don’t just forecast metrics but simulate trajectories. Intervention agents don’t just recommend actions but calculate precise interventions with calculated tradeoffs. Optimization agents don’t just suggest improvements but restructure topology with predicted consequences.

This is genuine autonomy—not because the AI makes decisions independently of human judgment, but because it understands behavior well enough to predict consequences and select interventions that achieve desired outcomes. Without behavioral models, agents are sophisticated if-then rules. With them, agents become adaptive controllers that reason about system dynamics.

The Integration

The three pillars aren’t separate capabilities to be implemented independently. Their power emerges from integration.

Time machine capability combined with a conversational interface creates an immersive diagnosis through dialogue. Walk me through the failure, the operator asks, and the AI reconstructs system state, advances through the timeline narrating the dynamics—here the input rate jumped, here pressure began accumulating, here the queue reached saturation, here backpressure propagated upstream—translating temporal simulation into experiential understanding.

Time machine capability combined with behavioral modeling enables counterfactual analysis for optimization. What if we had more capacity? The AI runs a simulation with modified parameters, describes outcomes: the surge would still exceed capacity, but the buffer growth rate reduces, a critical threshold is hit later, and additional minutes become available for adaptive response. Temporal simulation plus dynamic models yields what-if exploration.

Conversational interface combined with behavioral modeling creates collaborative intervention planning. The AI describes the situation: boundary diverging, pressure accumulating, a critical threshold approaching. The operator asks for options. The AI uses behavioral models to calculate interventions, presents each with quantified tradeoffs: throttle this inlet by this percentage, expect these consequences; scale this component by this factor, expect these costs and benefits; activate this alternative path, expect this complexity and this outcome. The operator decides, the AI executes, and both monitor for effectiveness.

All three together enable what we might genuinely call autonomous operations. Behavioral models perceive current dynamics and predict trajectories. Time machine capability simulates interventions and their consequences. Conversational capability negotiates with humans about autonomy boundaries and explains actions taken.

Imagine an AI agent operating within agreed boundaries. It perceives an input flow spike. Its behavioral model projects saturation in six minutes. It simulates intervention options. It checks its authority—scaling decisions within its autonomy boundary for this subsystem. It acts, provisioning additional capacity. It reports: divergence detected, scaled from three to five replicas, the system is stabilizing, buffer depth peaked and now draining, expected return to baseline in three minutes. The human reviews confirm an appropriate response; no intervention is needed.

This is agentic intelligence: perception, reasoning, action, and communication integrated into an autonomous yet transparent operation. Not AI that replaces human judgment, but AI that extends human capacity into domains where cognitive limitations would otherwise leave us helpless.

The Gap

Nothing I’ve described is speculative. The theoretical foundations have been clear for decades. The computational resources to implement them exist. The need is increasingly urgent as system complexity exceeds human cognitive capacity. And yet current AI observability provides none of it.

What it provides instead: pattern recognition on metrics, log clustering and similarity search, trace analysis for request flows, correlation of events across services, natural language interfaces to query these artifacts, and automated responses that trigger runbooks based on pattern matches. All of this accelerates existing practices. None of it addresses the fundamental gap.

No time machine. You can query historical data, but you can’t reconstruct system state at arbitrary points. You can’t simulate forward from past states to understand trajectories. You can’t explore counterfactual scenarios. Historical queries give you artifacts. They don’t give you a temporal experience of system dynamics.

No situational conversation. You can ask about logs and metrics, but you can’t discuss system dynamics in terms of flows, pressures, or stability. You can’t explore what’s happening versus what was logged. You can’t negotiate intervention strategies with calculated tradeoffs. Natural language interfaces give you better queries. They don’t give you situational intelligence.

No behavioral models. You can find patterns in data, but you can’t model how components interact dynamically. You can’t calculate precise interventions based on dynamic equations. You can’t predict trajectories of diverging boundaries. You can’t simulate alternative topologies before implementation. Pattern recognition gives you a correlation. It doesn’t give you a mechanistic understanding.

The architectural void is profound. Current AI observability sits on traditional telemetry infrastructure: OpenTelemetry capturing logs, metrics, traces; data lakes storing massive volumes; large language models analyzing patterns in stored data. The perceptual substrate that’d make the three pillars possible simply doesn’t exist. There’s no representation of holonic boundaries and nested structure. There’s no capture of flow circulation across inlets and outlets. There are no stability classifications of subsystems. There are no topological configurations or their mutations over time. There are no dynamic behavioral models of interactions.

Without this substrate, AI operates at the artifact level. It can be a remarkably intelligent librarian, finding patterns in recorded events with impressive speed. But it can’t perceive the system as a living organism, can’t feel the circulation, and can’t anticipate the dynamics. It reads about the patient’s history, but can’t take their pulse.

The Choice

In 2015, a decade before AI observability became a market category, this vision existed. The three pillars were articulated not as predictions but as architectural analysis: what would genuine machine intelligence about operations actually require? Not faster log search. Not smarter alerting. But temporal immersion, situational translation, and behavioral modeling—capacities that together would allow machines to perceive systems as they actually exist, as dynamic organisms rather than collections of artifacts.

The field chose a different path. It chose to optimize existing practices rather than reimagine foundations. It chose pattern matching over modeling, query acceleration over temporal simulation, natural language interfaces to databases over genuine situational awareness. And here we are, a decade later, layering large language models on the same broken substrate, making the same fundamental mistake at higher levels of sophistication.

The people who pay for this choice aren’t the vendors or the investors. They’re the engineers on call at 3 AM, drowning in alerts, scrolling through logs, trying to construct understanding from fragments while the system degrades. They’re the operators blamed when cascades escape their ability to perceive and prevent. They’re the teams burned out by the cognitive load of managing complexity that exceeds human capacity to grasp, using tools designed for simpler times.

We owe them better. We owe them tools that extend their perception rather than merely accelerating their searches. We owe them partners who understand dynamics rather than merely recognizing patterns. We owe them the three pillars: time travel through system states, conversation about situations rather than artifacts, and models that capture behavior rather than just correlating events.

This isn’t impossible. It requires a different architecture, not an impossible architecture. The perceptual substrate can be built. In fact, it’s been built. The behavioral models can be implemented. The conversational interfaces can be created. The integration can be achieved. The question isn’t feasibility but priority—whether we continue optimizing the path we’re on or turn toward the destination we need.

We’ve already lost a decade. The complexity has continued to grow while our approaches have merely accelerated. AI has arrived, promising transformation, and we’re using it to do the same things faster—the same forensics, the same artifacts, the same gap between what systems do and what we can perceive.

Will we lose another?

Coda

The mid-century vision of intelligent machines cooperating with humans to manage complex systems wasn’t naive. It was prescient. What it required—machines that could move through time, conversations that translated dynamics into situations, models that captured behavior—these weren’t aspirations but architectural prerequisites.

For decades, we lacked the computational power, the theoretical frameworks, and the practical necessity to build this. We built instead what we could: systems that monitored components, collected events, and alerted on thresholds. We debugged by reading logs and reasoning through artifacts. It was enough, barely, for the complexity of the time.

That era has ended. System complexity has exceeded human cognitive capacity for artifact-based reasoning. AI has created the possibility for machine perception of dynamics. The convergence makes the three-pillar architecture not merely feasible but necessary.

The question that remains is one of will rather than capability. Do we continue building AI that reads logs faster, or do we build AI that perceives systems as they live and breathe? Do we continue asking people to synthesize understanding from fragments, or do we extend their perception into the dynamics that matter? Do we continue blaming operators for failures they couldn’t perceive, or do we give them the means to perceive?

The three pillars stand as both invitation and challenge. They describe what is needed. They illuminate why current approaches fall short. They chart the path that wasn’t taken a decade ago and could still be taken now.

The future isn’t coming. It’s been waiting. It’s time to build it.