The term “observability” is ubiquitous in software engineering, yet a profound misunderstanding clouds its current practice. Observability isn’t what most organizations are doing—it’s what they think they bought. What they’re engaged in is often mere telemetry plumbing, a far cry from genuine system sense-making.

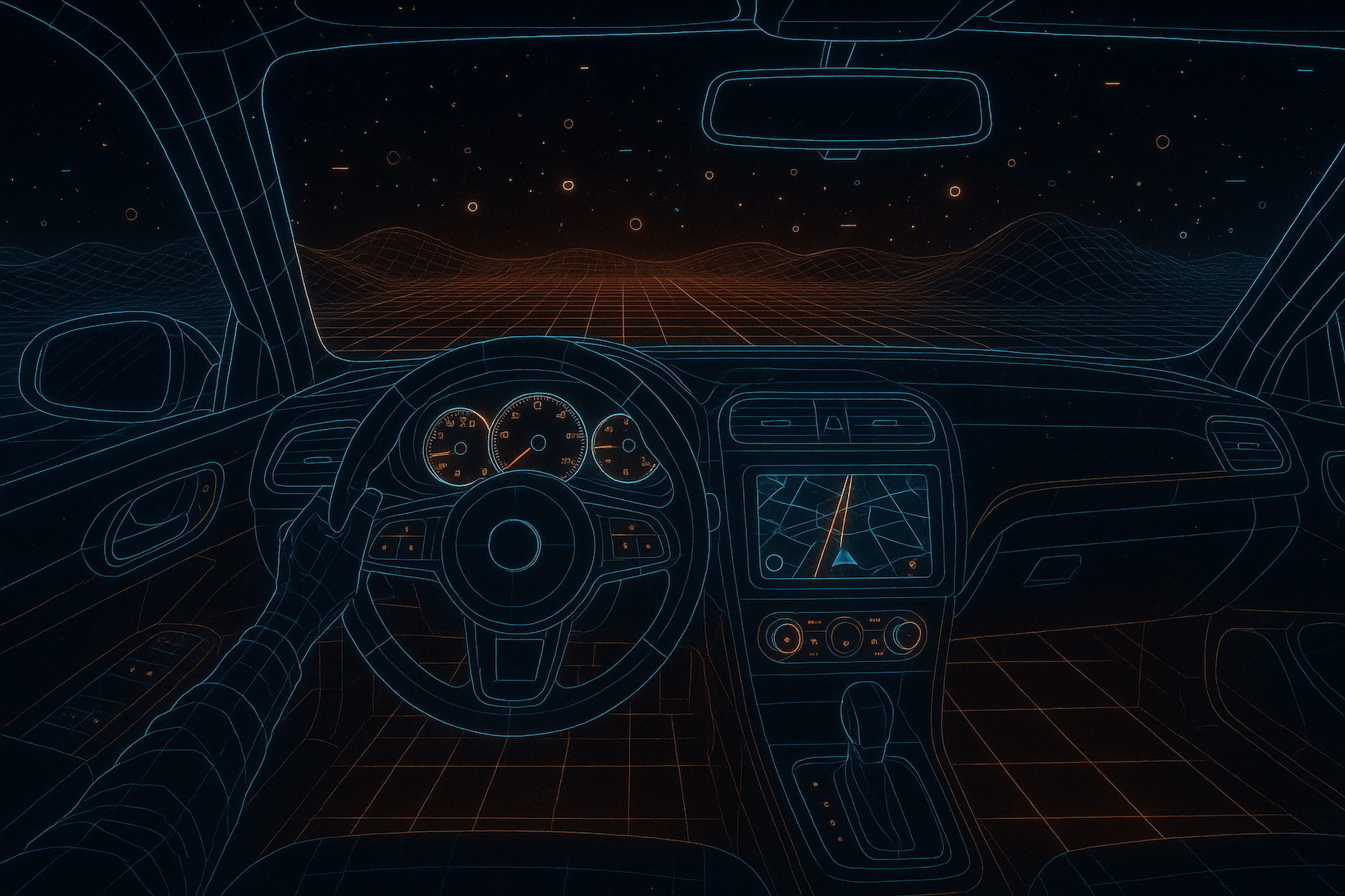

Imagine sitting in a car. The dashboard is beautifully lit, gauges flickering. The speedometer, though reading zero, is perfectly accurate. A GPS map gleams on the console. The steering wheel turns smoothly. Rear-view mirrors offer a pristine view of what’s behind them. You feel in control. But the car isn’t moving. It’s bolted to the ground. There are no wheels, no road, no traffic, no situation to respond to. And yet, we tell ourselves we’re driving.

This mirrors the state of observability in many modern software teams today.

This illusion has teams surrounded by telemetry—a brightly lit dashboard, a wheel to grip, a rear-view mirror full of logs, metrics, and traces—but provides no actual traction on the complexities of their systems. What we’re calling “observability” is frequently nothing more than extensive instrumentation and passive data collection.

We’re sold a myth, and the industry has quietly redefined a potent concept into something far more superficial.

Observability, properly understood as the capacity of a system to reveal its internal state through its outputs, enabling deep inference, has been conflated with simply “exporting logs, metrics, and traces.” This hasn’t just diluted the term; it’s gutted its power. This misdirection leads many well-intentioned teams into a frustrating and inefficient cycle:

- Instrument Everything: An exhaustive push to gather data from every conceivable component.

- Collect All Possible Data: A deluge of telemetry, constrained more by budget than by strategy.

- Visualize on Dashboards: Acres of graphs and counters are born, creating an illusion of insight.

- Sift Through Low-Signal Telemetry: Engineers become digital archaeologists in vast data graveyards.

Nowhere in this common cycle do most teams systematically build models, make robust inferences, or develop true situational awareness. If your system emits millions of metrics per second and no one truly understands what they signify in concert, you haven’t achieved observability—you’ve just created entropy. It’s a ritual without reflection, motion without movement, a sense of control without actual steerage. Teams stare at dashboards hoping for meaning to emerge, tuning alerts to symptoms, not causes, perpetually reactive.

It’s crucial to differentiate: Observability isn’t just data, tooling, or the rear-view mirror of past events. Yes, teams are observing. But true observability is a latent property, deliberately designed into a system that enables you to infer its current state in real-time, with enough fidelity to guide control. It’s about knowing what’s happening now, not just what happened five minutes ago. It demands more than data; it requires understanding. This means having:

- Meaningful Signals, Not Noise

- Compression of Signals into Meaningful Judgments

- State Inference & Condition Assessment

- Projection of Future State & Viable Control Paths

Few achieve this because the industry often hasn’t provided the tools or conceptual frameworks. Vendors sold telemetry pipelines and called it observability, then layered dashboards on top and called it insight.

As a cybernetician, my work has consistently aimed to simplify complexity and foster a genuine understanding of sociotechnical systems. True observability aligns with this: it should empower, not overwhelm. It requires us to move beyond the dashboard. We don’t need more panels; we need perspective. We don’t need faster metrics; we need models of system behavior. We don’t need prettier charts; we need context.

- Observability isn’t a dashboard

- Observability isn’t a log viewer

- Observability isn’t a trace explorer

Observability requires a situation. You can’t be aware of a situation unless it’s developing, and you can’t assess it unless your system provides signs of meaningful change.

It’s time to stop mistaking infrastructure for insight and to stop calling raw data “observability” before it earns that name. It’s time to stop pretending that turning a steering wheel matters if it’s not connected to anything.

The future of observability, if it’s to deliver on its original promise, must become interpretive. It must involve semiotics—the study of signs and their meaning. Systems should not only emit telemetry but participate in a meaningful dialogue with those who operate them. Observability must evolve from being a fire hose of undifferentiated noise into a sophisticated process of sense-making, signal compression, and state narration.

This calls for a paradigm shift, drawing on principles of systems thinking and cybernetics, focusing on human-machine interaction, intelligent process design, and tooling that facilitates true understanding. It’s about architecting for intelligibility, building systems designed to be understood.

A great misunderstanding has led to significant investment in activities about observability, rather than cultivating the discipline itself. Reclaiming the term and its practice means moving beyond telemetry plumbing to the more challenging, but vastly more rewarding, pursuit of true system sense-making. Only then can we confidently say we’re not just staring at a dashboard in a stationary car, but are actually navigating the road ahead, truly driving our systems.