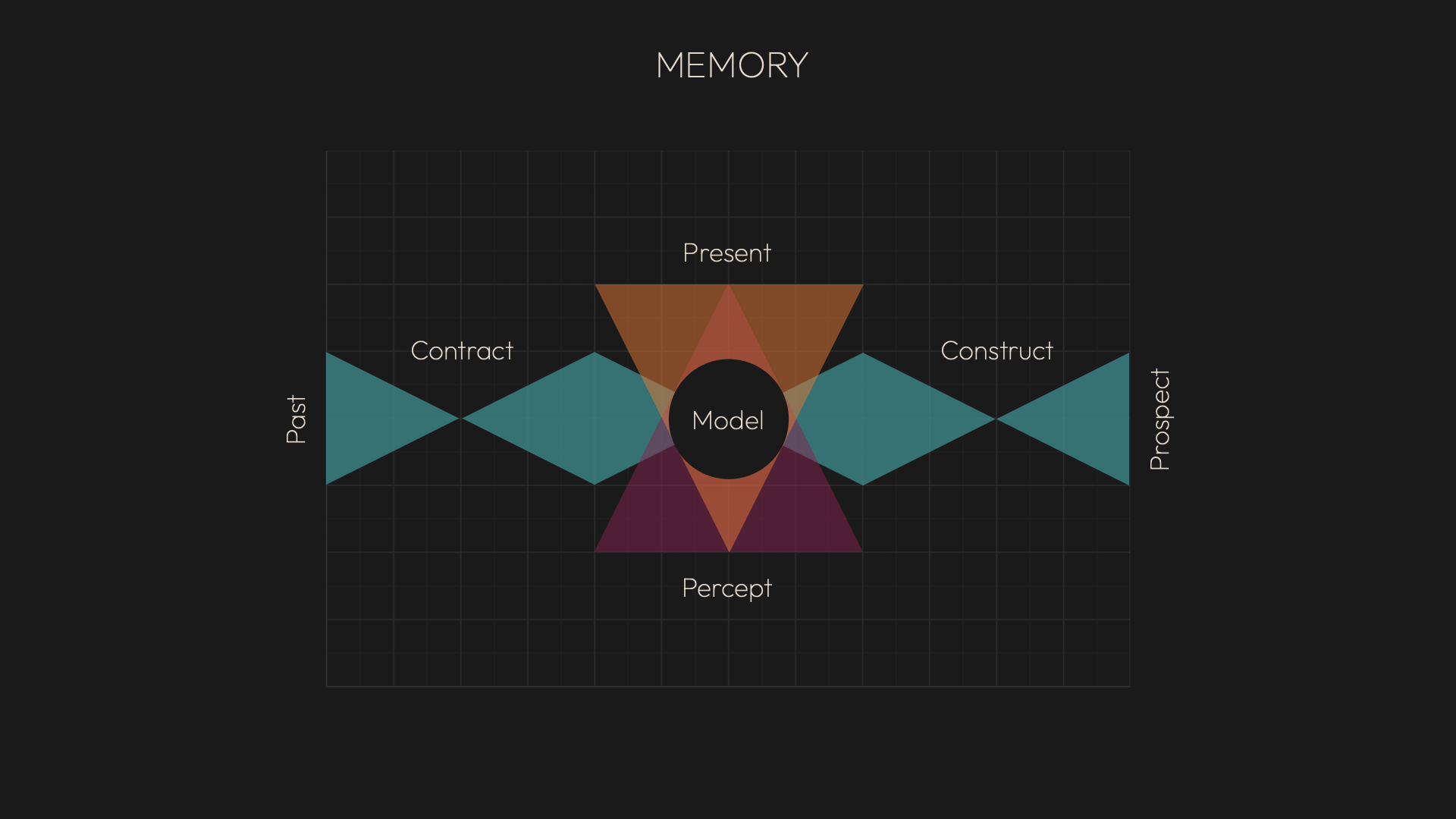

What if every act of communication, every flicker of thought, every mnemonic trace were less a perfect transmission and more a living breath? What if to express, to observe, to remember, is always to “forget”—to contract and compress experience—followed, inevitably, by an act of imaginative expansion, a reconstructive inhalation where meaning is made new again? This is the semiotic respiration: the ceaseless, rhythmic flow between compression and expansion, abstraction and reconstitution, forgetting and creative remembering. It isn’t simply about how information moves from sender to receiver, but about how meaning itself survives and is remade—how systems, minds, and cultures live through cycles of loss and recovery, selection and imagination.

Exhalation (Contract)

We let go, we forget, we encode, we compress. This is the “death” that makes room for new life, the pruning that allows the model to stay alive.

Inhalation (Construct)

We draw in, we interpret, we project, we imagine. This is the “rebirth” of meaning, the creative leap from fragment to whole.

Living Cycle

Every act of observation, memory, and communication is a crossing—never a perfect copy, but a reconstitution, a new synthesis.

At the center: Model—the living nexus, the self-in-time, the locus of sense-making. Below this is the Percept—the now, the ground, the inrush of sensation and signal. Above the model is the apex, the synthesizing moment where the present is reasoned, the future constructed, and perception anchored.

Compression, Abstraction, and Loss

To communicate is, fundamentally, to compress. We’re always forced to reduce the fullness of experience—rich, entangled, ineffable—into something portable, transmissible, survivable. This isn’t just a technological constraint, but an existential one. Whether through language, gesture, symbol, or data, what we send is always a reduction: a selection of differences, filtration of noise, an act of creative forgetting.

Abstraction is the art of this compression. To abstract is to see what’s common, to distill the general from the particular, and to shape a symbol from a sea of instances. In computational terms, abstraction is mapping many possible states onto a single form, reducing entropy to act, decide, or transmit.

Shannon’s information theory made this process visible in mathematics. By divorcing “information” from “meaning,” he revealed that what matters for transmission isn’t content but difference—the reduction of uncertainty, the economy of bits. Bateson, building on this, insisted that information is a “difference that makes a difference.”

Every abstraction is a cut, a sacrifice, a claim about what matters.

But there is a cost: abstraction always entails loss. The infinite particularity of reality is trimmed away for the sake of shareability, generality, and efficiency. Luhmann’s systems theory frames this as a selection from overwhelming complexity—systems must reduce the world to something they can manage, and meaning emerges from what is left behind, what isn’t forgotten. Each system, therefore, develops its codes (signs) and categories for what is considered meaningful, guiding its selective interaction with the environment.

While compression is a key outcome and function of abstraction, the process also involves structuring, relating, and creating new levels of understanding that aren’t merely reductive. Abstraction can lead to the emergence of novel concepts and properties that weren’t apparent in the constituent data. There’s a simplification here, an abstraction.

The Architecture of Understanding

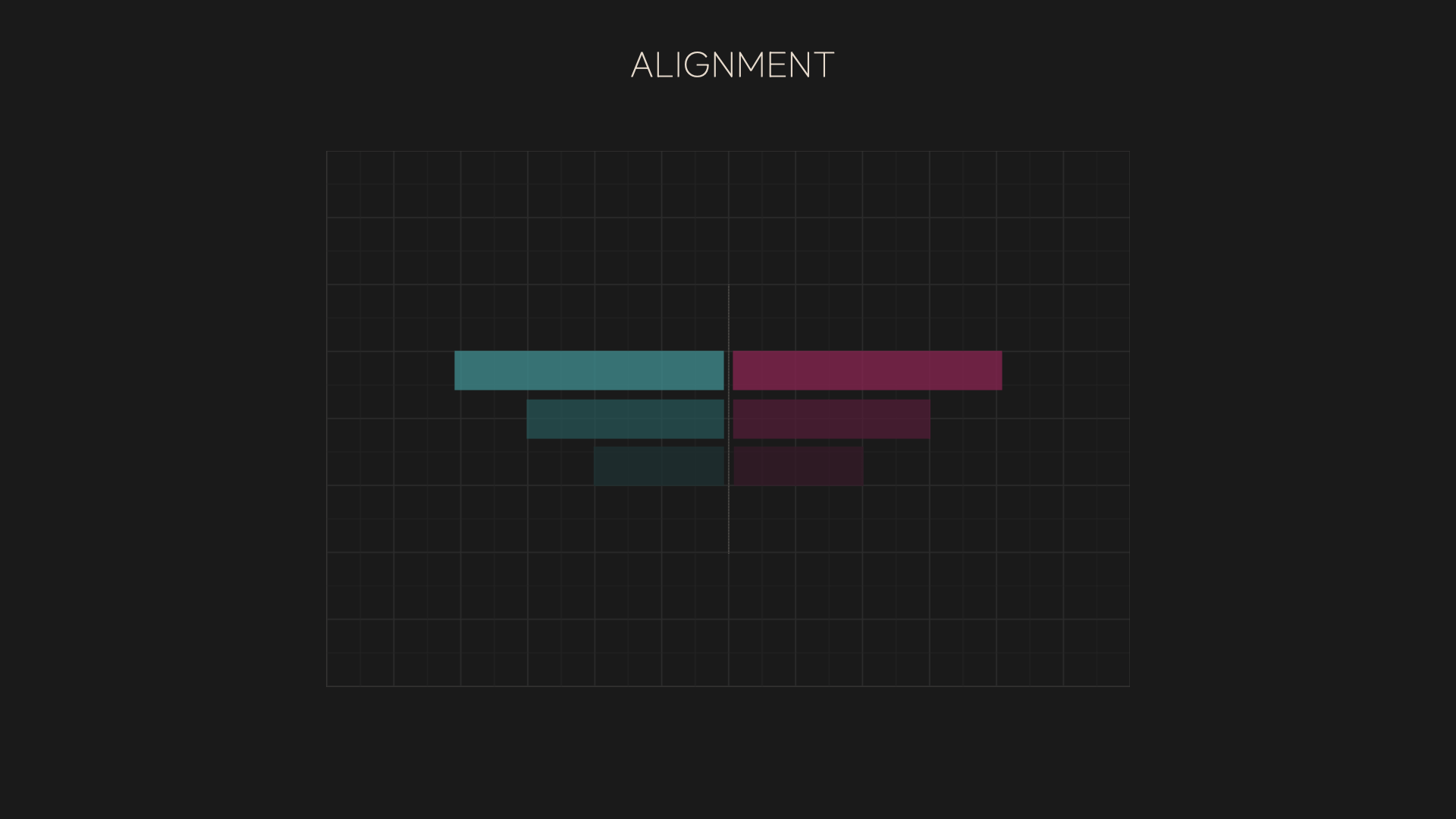

Every system—cognitive, social, technical—deals with complexity by layering. In computers, we build stacks: hardware, firmware, OS, protocols, and applications. Each layer hides detail from the next, making possible interoperability and modularity, but also introducing opacity and the risk of misalignment.

Information hiding is more than a design principle; it’s the condition of any living model. To function, the mind must ignore most of what it can remember and most of what it can perceive. Perception isn’t a mirror but a spotlight, a filter.

Memory isn’t a vault, but a breathing engine that contracts and constructs—continually shaping a model of self and world that’s never complete, never static.

Our living models are thus provisional, layered, and selective. They’re always at risk of missing the vital signal, of overfitting to the past, of mis-projecting into the future. The art is in knowing what to forget and what to build anew.

Our understanding of complex phenomena in any domain is inherently layered, with different levels of abstraction affording different kinds of legibility, actionability, and insight.

The principle of information hiding isn’t merely about the existence of layers, but a deliberate design strategy to encapsulate implementation details that are likely to change behind stable, well-defined interfaces. This has profound implications not only for how technical systems are built and maintained but also, by analogy, for how cognitive or social systems might manage complexity, evolve, and maintain stability in dynamic environments.

The partial forgetting inherent in communication is an adaptive form of information hiding. Details deemed irrelevant to the immediate communicative goal or the recipient’s likely context are implicitly or explicitly “hidden” or shielded. This prevents cognitive overload for the receiver and allows the sender to focus the message on its intended core. Such selective omission, if done effectively, facilitates clearer transmission of the intended essence, even as it necessitates imaginative reconstruction by the receiver to fill in the deliberately elided details based on their understanding and context. Forgetting isn’t a defect but a strategic element of efficient and effective communication.

Mapping the infinite variety of a complex environment into a model and controller is often impossible or prohibitively costly. Therefore, effective control frequently involves “managing variety by intelligent compression.”

Language and Metaphor

Language is our greatest tool of compression. A word isn’t a thing, but a signal—a portable, ambiguous, context-sensitive act. A single phrase can compress a story, a culture, or a command.

Metaphor is the engine of abstraction, as Lakoff and Johnson have shown. We understand the abstract through the concrete: “time is money,” “argument is war,” and “love is a journey.” These aren’t just poetic devices, but the living scaffolding of thought. Yet every metaphor also conceals as it reveals: to see time as money is to miss what can’t be spent or saved. The compression is both generative and limiting.

The meaning of a word is its use. In every context, in every utterance, language is action. It’s a prompt to perception, to memory, to projection. Words don’t merely name—they reshape what’s thinkable, what’s possible.

The tapestry woven here, in connecting information theory, systems theory, semiotics, and cognitive linguistics, isn’t merely a stylistic flourish but a methodological necessity. Communication, as a multifaceted phenomenon, involves the transmission of information (information theory), occurs within and between systems (systems theory), relies on signs and symbols (semiotics), and is processed and generated by cognitive agents (cognitive science and linguistics).

The Breathing Cycle of Meaning

Peirce’s semiosis finds its rhythm here: each interpretation becomes a new sign, each model a fresh premise for the next act of meaning. Eco’s “openness” of the work, Luhmann’s three selections of communication, and Hofstadter’s “analogy as the core of cognition”—all converge on this point. Meaning isn’t transmitted but breathed into being.

To remember isn’t merely to retrieve; it’s to shape, to renew, to let go, and to dream. Memory is the original act of observability. It’s the art of shaping presence from the memory traces of what was, and the outline of what might be.

The Trees of Convergence

What’s gained by abstraction? The ability to align across domains—to recognize the “tree of convergence” where diverse branches (ideas, systems, sciences) share a trunk of a pattern, form, or relation. Such a “network” isn’t just wires or neurons; it’s the structure of connection itself, as valid in biology as in sociology, technology, or narrative.

The same is true of “feedback,” “system,” and “market.” These abstractions aren’t mere generalities—they’re cognitive technology, allowing us to transfer insight, innovate, and synthesize.

But every abstraction is a trade-off. The more universal, the less precise. The more portable, the less it carries from its origins. The art is to find the level of compression, of generality, that serves both understanding and action.

The Challenge

The choices of what to contract, what to construct, what to forget, and what to project—these are acts of responsibility and creativity. Whose past is remembered? Whose futures are imagined? Which signals become noise, and which noise becomes a new signal?

In communication, design, memory, and observability, the deepest art isn’t to maximize retention or transmission, but to shape the living model—to cultivate a system that is both resilient and open, anchored and imaginative.

The Art of Observability, The Breath of Meaning

Every map isn’t the territory; every model is a provisional truth. What endures isn’t the perfect preservation of the past, but the rhythm of becoming—the living breath that lets us observe, make sense, let go, and begin again.

In every cycle of contraction and construction, forgetting and imagining, the semiosis gives rise to new meaning. The vitality of a system, a mind, and a society depends not on what is remembered, but on the art with which it breathes.

To observe, to remember, and to understand, is to breathe with meaning.

This is the living art at the heart of observability.

And in every breath, the model is made new.