The Paradox

In the pursuit of efficiency, a directive to simplify can paradoxically lead to chaos and increased complexity, especially when such a mandate cascades through the hierarchical layers of a company. Each department and team interprets and implements the order through its lens, often without a unified vision.

What starts as a well-intentioned effort to streamline operations quickly devolves into conflicting initiatives. Processes are hastily dismantled, roles are redefined overnight, and long-standing systems are upended—all in the name of simplification. The result is a perfect storm of disruption: communication breakdowns, misaligned objectives, and a tangled web of half-implemented changes. In no time, the organization must grapple with a new layer of complexity born from the attempt to eradicate it.

Emergent Complexity

When an organization-wide initiative, such as simplification, is disseminated to all actors within a complex system, each actor interprets the message and initiates changes, typically at the boundaries where they interface with other actors or collectives. However, each actor operates from a limited perspective—myopic rather than holistic. With each actor interpreting the message based on its local context, priorities, and constraints, without a unified perspective, the resulting changes are likely to be inconsistent or contradictory. This can lead to friction, as interconnected actors may now have conflicting expectations regarding processes, priorities, or resources. Ironically, while each actor aims to simplify, the organization as a whole experiences a rise in systemic complexity. Because each actor’s actions are taken independently and without a full understanding of the organization’s broader needs, new dependencies and failure points are introduced. Local optimizations then aggregate into a globally more complex system.

This phenomenon bears similarities to other intricate adaptive systems, such as the release of stress hormones like cortisol, which initiates a cascading effect throughout the body. If the stress becomes excessive or prolonged, it can cause various systems to overreact or work in conflict. The resulting lack of coordination inevitably leads to amplification, feedback loops, and systemic problems. This emphasizes the significance of complex systems mechanisms that can dampen or coordinate responses to prevent such overwhelming cascades. For instance, feedback inhibition regulates hormone levels in the body. Similarly, organizations can implement buffering mechanisms and communication channels to maintain coherence and alignment when introducing significant signals or initiatives.

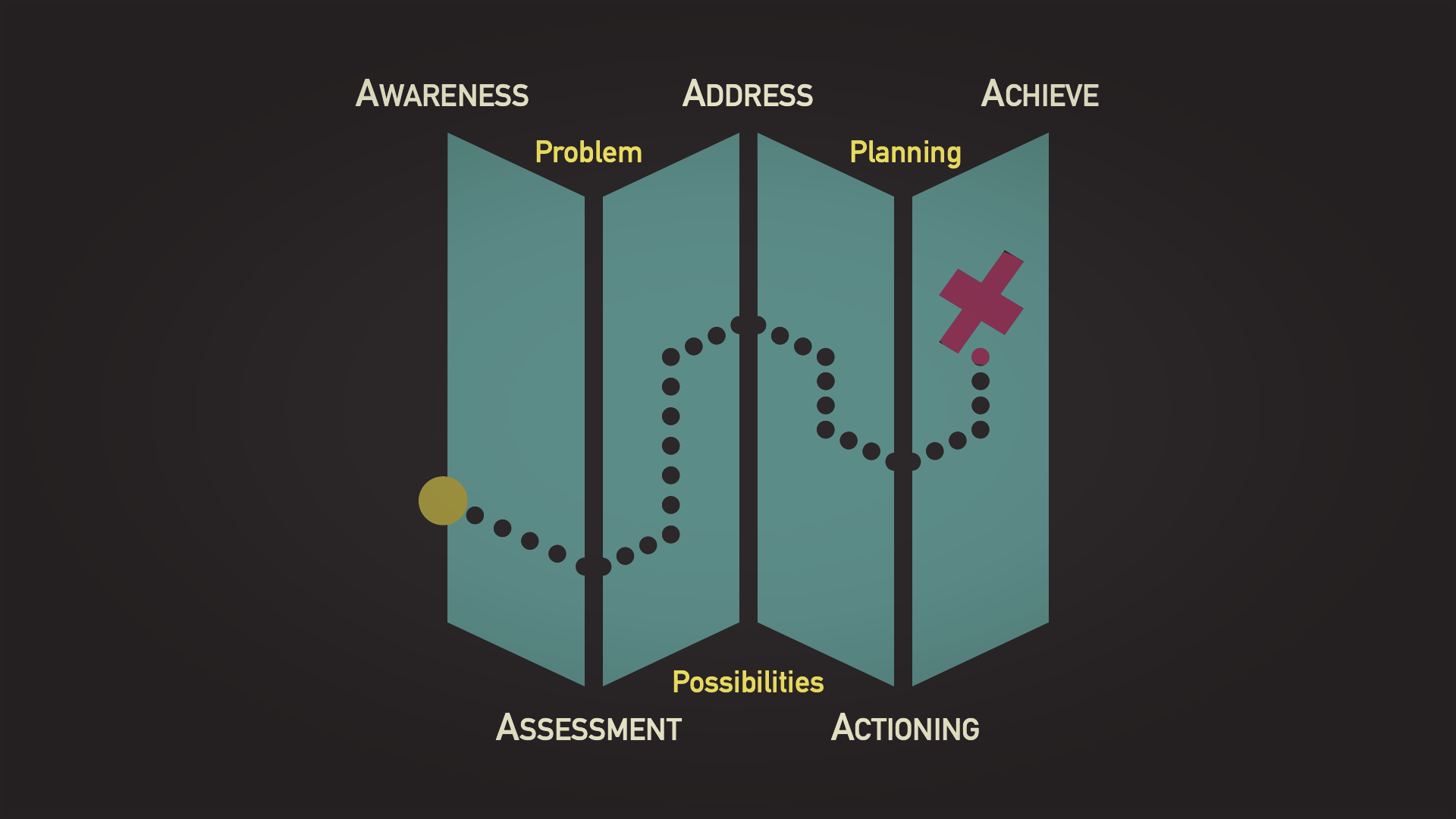

To more effectively coordinate the simplification process across a network of adaptive actors, strategies can be implemented to manage the dissemination of signals and ensure more unified responses. Key elements include staggering the rollout, facilitating collaboration, and incorporating feedback mechanisms.

Instead of broadcasting the signal to all actors simultaneously, we can adopt a staggered approach, where we select a subset of actors or collectives to serve as pilots or early adopters. Based on feedback, we refine the signal before disseminating it to a broader network. The selection can focus on actors or collectives with strong interconnections or central roles within the organization. These actors can then guide and influence neighboring actors, fostering a more cohesive response and mitigating potential overreactions in the periphery. If feedback indicates overreaction or runaway changes, we can implement dampening mechanisms such as temporary pauses, additional oversight, or reassessment phases.

By staggering signal dissemination, fostering localized collaboration, integrating adaptive feedback loops, and employing damping mechanisms, we can steer the process of simplification in a way that mitigates overreaction and promotes coordinated change across the network. This not only supports coherence but also creates a more resilient network capable of adapting to the demands of simplification.

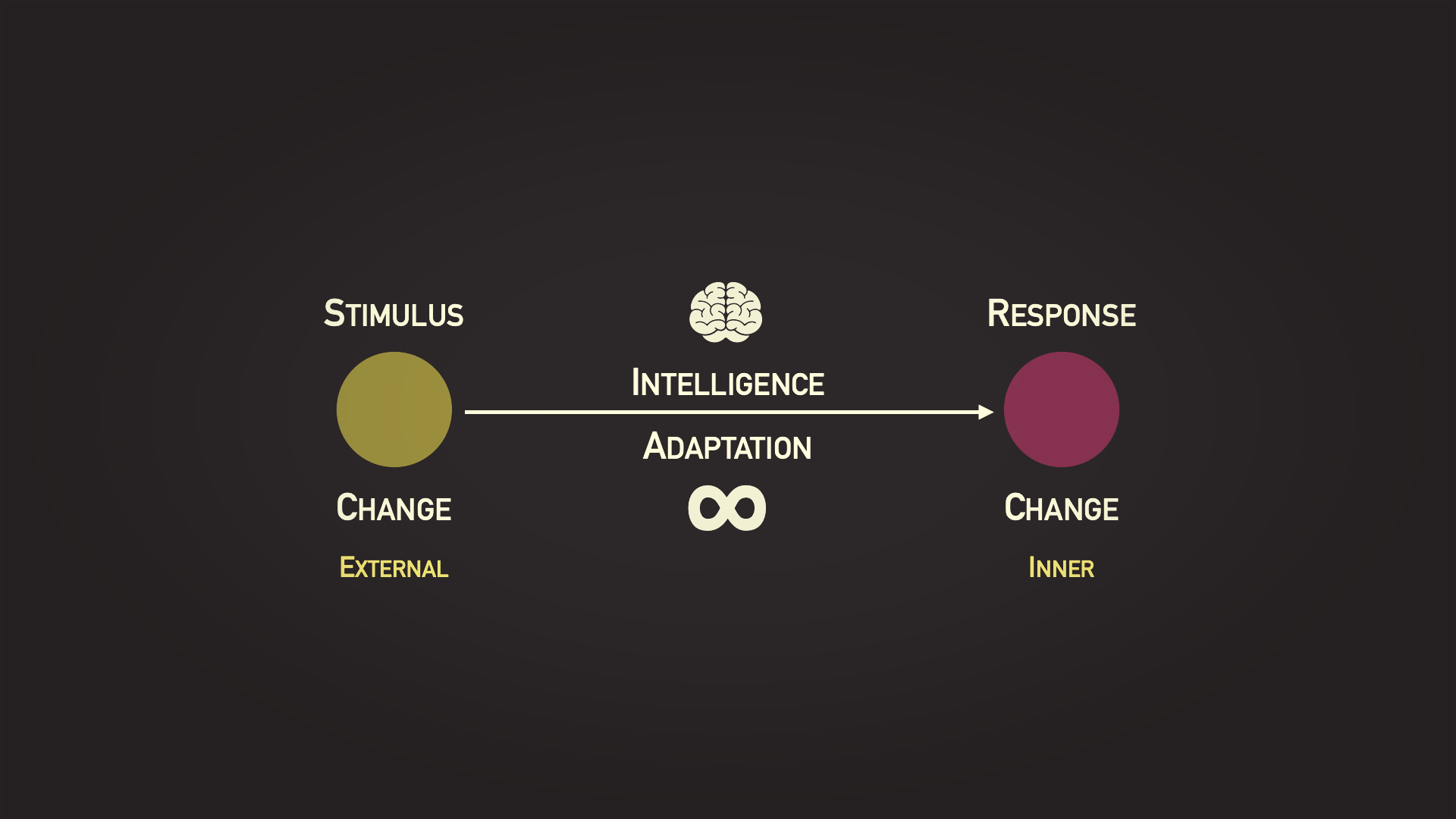

Mixing Channels of Communication

One of the most significant challenges in communicating simplification initiatives is the conflation of awareness and adaptation. Effective systems require distinct channels for different types of information flows. Stafford Beer, in his cybernetic work, made a crucial distinction between communication and control signals. He differentiated between algedonic signals, which are alert signals that disseminate critical information throughout the system, and control signals, which are specific directives that only certain subsystems are required to execute. Algedonic signals ensure that all stakeholders are informed of critical changes or potential disruptions, but they do not necessarily prompt immediate action. Control signals, in contrast, are precise instructions for actors who must implement changes or adapt based on the prevailing context. When channels are mixed, there is no attenuation of signals to the appropriate audience.

Mixing channels reduces the system’s ability to differentiate and appropriately respond to different types of signals. An example of this can be found in immature IT organizations where every signal, even one of compliancy, is immediately promoted to an incident, flooding operational dashboards with noise.

In the realm of social systems theory, Niklas Luhmann explored the concept of communication types within complex systems. Luhmann observed that the interplay of awareness channels, intended for general dissemination, with channels of obligation, directed to those obligated to take action, can lead to confusion and inefficiency. This arises because the recipients lack clarity about the intended purpose of the message. When a message carries both informational and obligatory content, it becomes ambiguous to the recipient, leading to misunderstandings, delays, or even inaction.

Shared Understanding

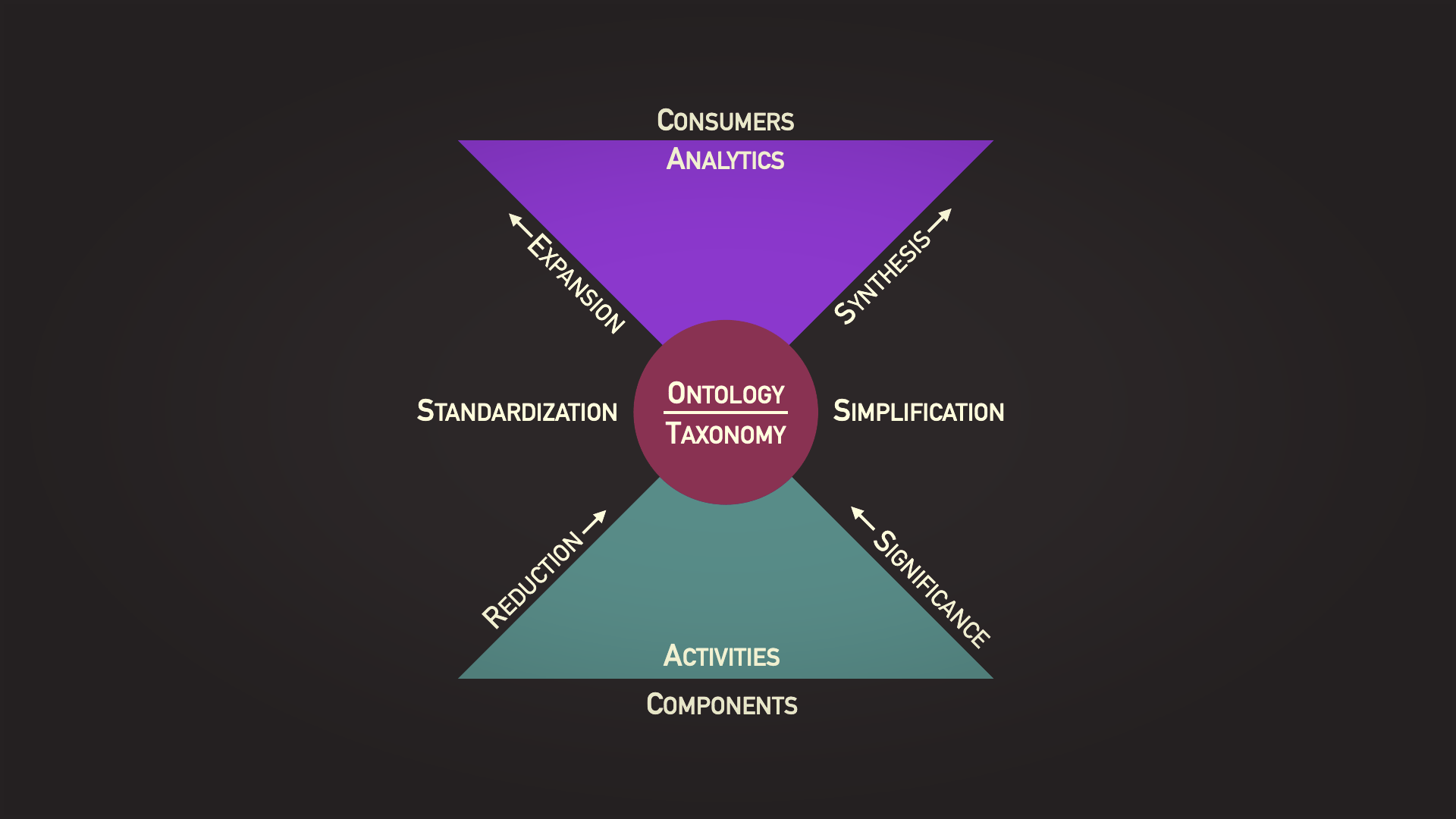

Establishing a shared understanding of simplification is crucial at the start of any simplification initiative.

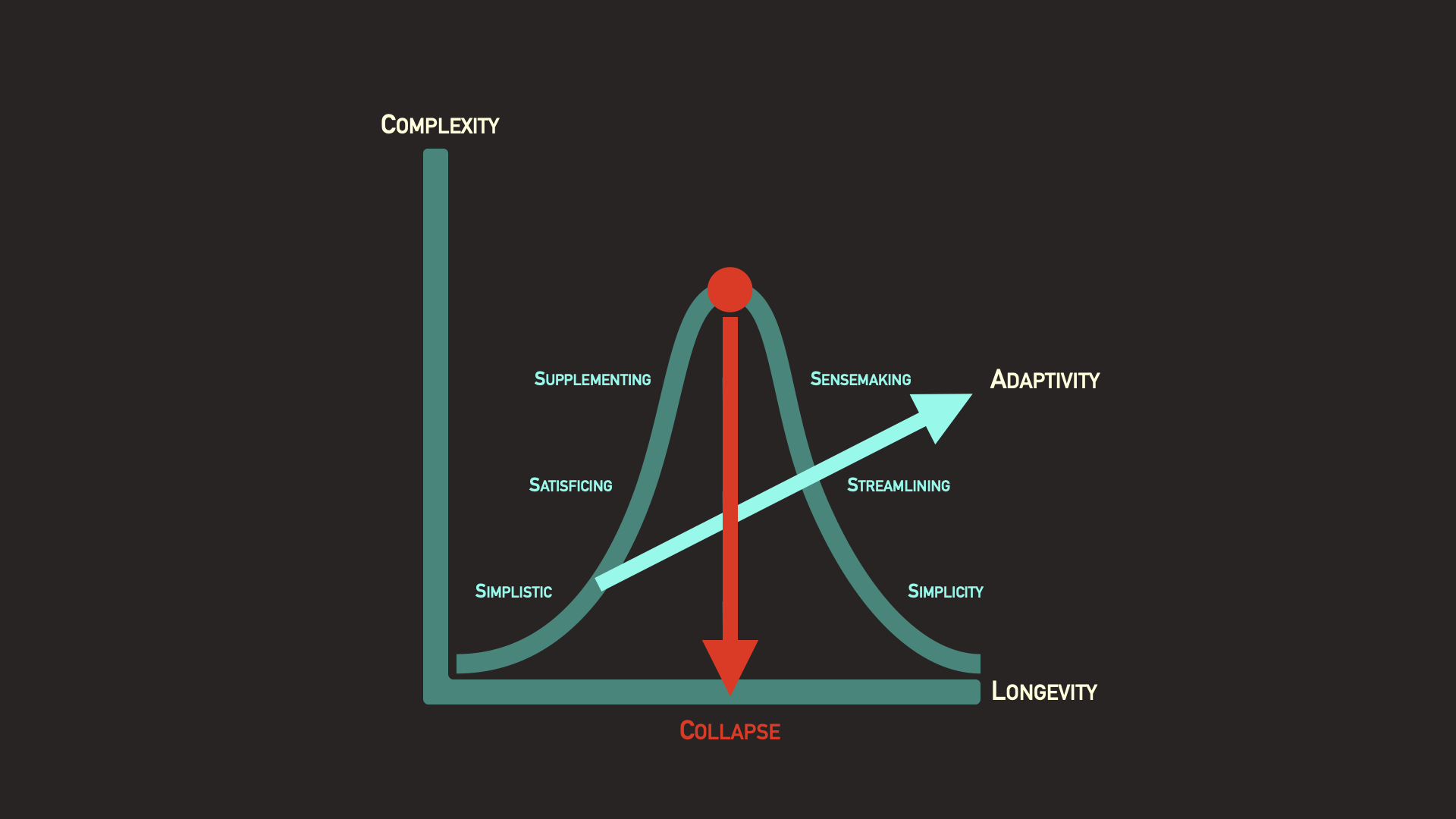

Many organizations lack a comprehensive grasp of simplification and confuse it with related concepts like streamlining, standardization, rationalization, and optimization. In socio-technical systems, simplification and streamlining are distinct yet interconnected concepts that impact system performance and user experience. Simplification reduces complexity by ensuring each component serves a fundamental purpose, making the system more understandable, user-friendly, and adaptable. Streamlining enhances efficiency within an existing structure by optimizing processes or eliminating bottlenecks to reduce waste and speed.

Simplifying a socio-technical system reduces cognitive load and enables easier adaptation to change. Simplification aligns with resilience by ensuring the system can handle unknowns and adapt to new contexts, not by doing everything faster, but by keeping things understandable and manageable.

Streamlining aims to speed up processes, minimize redundancies, and optimize workflows. However, this approach may conflict with the requirements of human users who need time to comprehend and adapt to changes. While streamlining can enhance efficiency, it can also result in oversimplification, eliminating essential elements for flexibility and resilience in the pursuit of speed and cost reduction. Thoughtful simplification preserves these qualities by concentrating on essential elements and reducing unnecessary complexity without compromising the system’s ability to handle diverse and unpredictable situations.

Simplification through abstraction conceals complexity and facilitates system management. Streamlining, on the other hand, is facilitated by optimization, which concentrates on efficiency. Optimization frequently involves standardizing processes and components to minimize variation and maximize reuse, leading to a streamlined system with fewer adjustments. However, optimization does not inherently reduce complexity.

Overfitting and premature optimization can result in rigid systems compromising flexibility and adaptability for short-term efficiency gains. In the socio-technical context, this is relevant as user requirements and environmental factors can fluctuate, making highly optimized systems vulnerable to challenges in adapting.

Striking a balance between simplification, standardization, streamlining, and related approaches requires a holistic view of the system and an understanding of how these elements interact and impact one another.

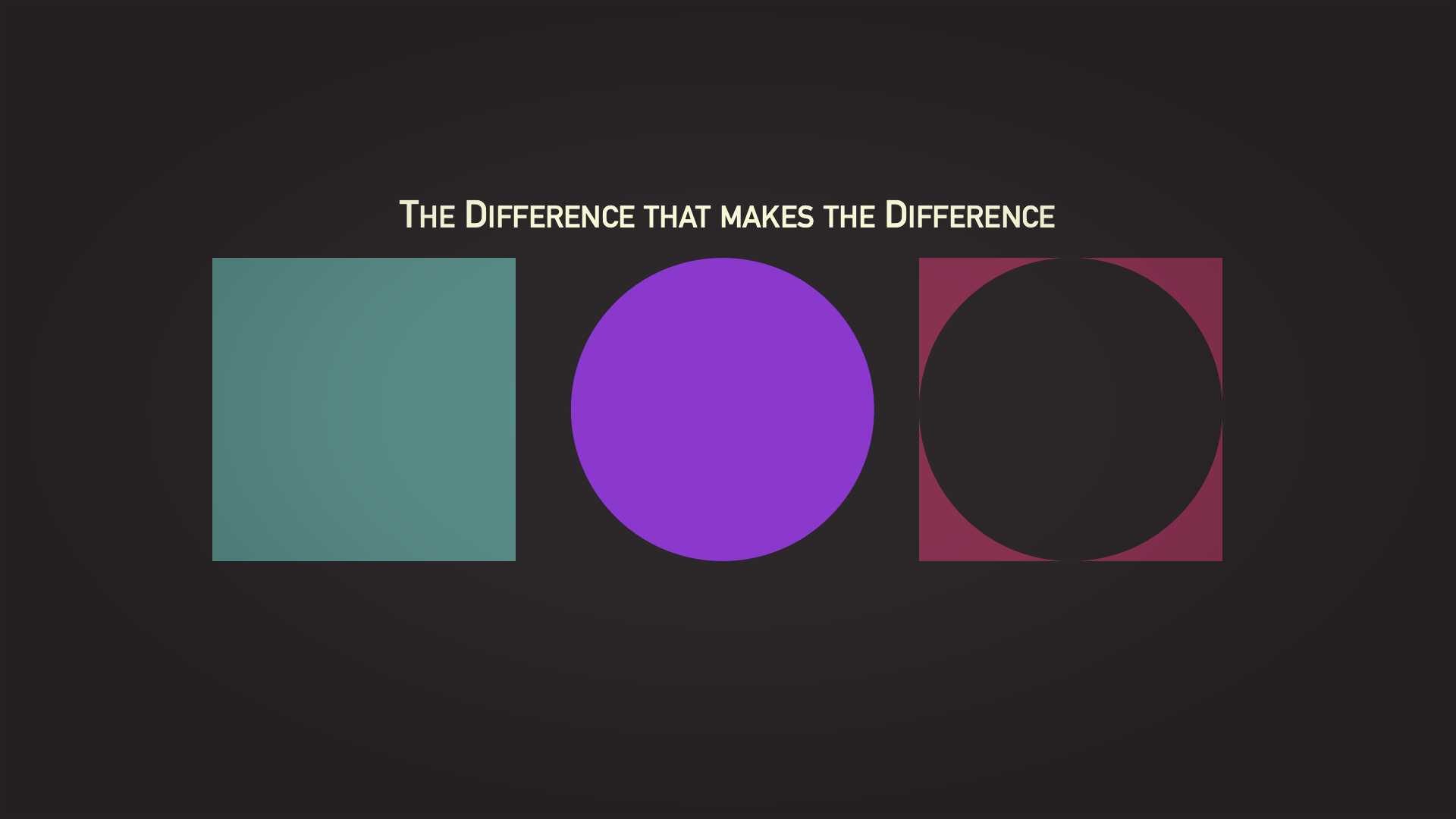

The Difference that Makes the Difference

Simplification, a conceptual and strategic approach, involves reframing the system’s purpose, examining assumptions, and making it more understandable and intuitive. This process may alter the system’s high-level functions and structure. Streamlining, a tactical approach, focuses on removing inefficiencies and expediting processes. It enhances the system’s functioning without changing its underlying structure or purpose. Understanding when to apply each approach is vital for designing a sustainable and adaptable strategy that optimizes the system’s performance in the present while preparing it for the future.

Simplification is a top-down approach that reevaluates a system’s structure and fundamental components. Streamlining is a bottom-up approach that optimizes specific processes or workflows. These strategies are effective in contexts with both a strategic layer and an operational layer. Simplification may require bottom-up feedback to identify overly complex areas. Streamlining initiatives can uncover opportunities for simplification if inefficiencies arise from systemic issues.

Simplification demands a broader systems awareness, encompassing the interactions, dynamics, and impacts of changes across various layers and components. This complexity requires collaboration and cooperation among different actors and collectives to ensure that any changes align with the overarching goals and integrate seamlessly throughout the organization. In contrast, streamlining is more localized and can commonly be achieved independently within specific areas, or “leaf nodes,” of an organization. It focuses on optimizing individual processes or tasks rather than rethinking their broader system context.

The Transmogrification of Simplicity

When management undertakes a significant simplification of the landscape, it inevitably leads to heightened operational streamlining efforts at lower levels. This phenomenon is particularly pronounced when communication is unclear, there is a misalignment of goals, and inadequate monitoring and feedback mechanisms are in place. Abstract concepts such as “simplification” can be challenging to translate into concrete actions for many, leading managers to interpret such a directive through the lens of their immediate responsibilities. These managers are typically more proficient in process management and less adept at systems thinking, which is a prerequisite. They prioritize quick, visible improvements over longer-term, systemic changes. As goals cascade down, the scope of control typically narrows, resulting in simplification being reinterpreted as streamlining of what is locally controlled. When this occurs, there is a risk that the overall effort becomes a tactical exercise in efficiency rather than a transformative opportunity. Bridging the conceptualization and interpretation gap necessitates deliberate efforts to preserve the strategic purpose of simplification while ensuring that operational actions harmonize with the broader vision. The management challenge extends beyond effectively communicating the concept of simplification; it entails ensuring consistent application across diverse organizational contexts, ultimately guaranteeing the integrity of the original vision throughout the implementation process.

The Elusiveness of Simplicity

Achieving simplicity is a complex and elusive goal that requires a delicate balance to avoid the pitfalls of oversimplification or superficial streamlining. True simplicity is characterized by its profound clarity and depth, yet it can be challenging to identify and measure due to its abstract nature. Simplicity involves finding the essence of a problem and addressing it in a way that reduces unnecessary complexity while preserving essential details. It enhances clarity and improves usability, efficiency, or understanding without eliminating crucial elements. Simplicity emerges through iterative cycles of testing, receiving feedback, and refining a design or process. By progressively eliminating unnecessary elements, a solution is realized that is both efficient and effective. Constraints can guide the search for simplicity by limiting the scope and encouraging creative solutions. Instead of simply eliminating features, simplicity should respect the function and context of the solution, balancing necessary functionality with a clear understanding of usage. This ensures that what remains is both purposeful and sufficient for the intended context.

Simplicity emerges from patterns or relationships that are not immediately clear. To achieve simplicity, one must comprehend the entire system and understand the interactions between its components. This understanding comes from repeated iterations of observation, reasoning, and refinement. Unfortunately, it is common for a design to become more complex before simplifying. This happens because exploring different angles and possibilities, which usually leads to adding components, can make it feel like the direction is away from simplicity instead of toward it. Each step might seem small and subtle, but collectively they contribute to the final attainment of simplicity.

Simplicity: A Journey, not a Destination

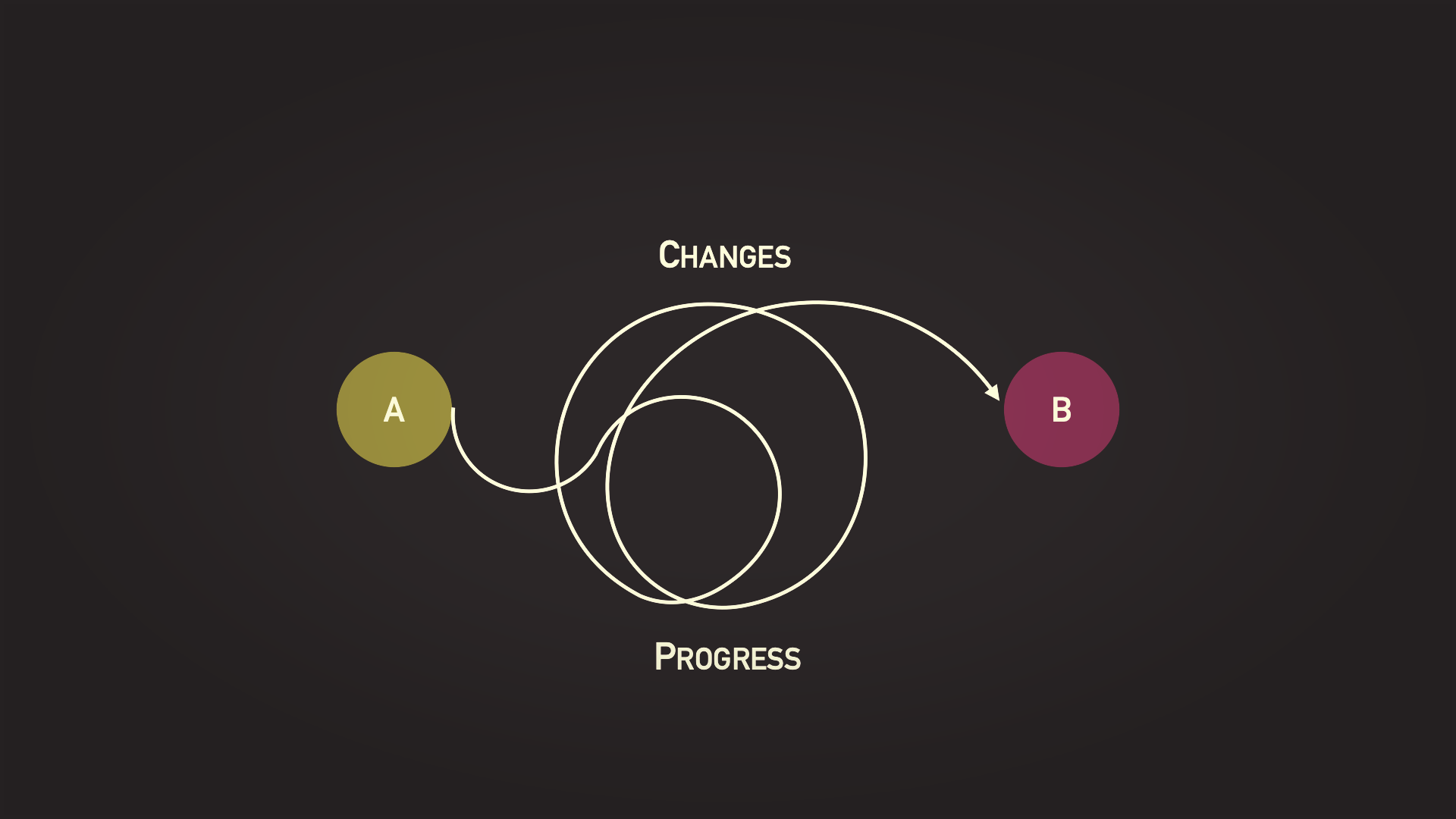

Achieving simplicity is not a one-time endeavor; it requires continuous evaluation and adaptation.

A solution must be regularly revisited to ensure that it still aligns with the fundamental requirements and remains efficient and effective as circumstances change. Frequent feedback from users or stakeholders is essential in determining whether an approach to simplicity is resonating, helping to reveal aspects that may still be overly complex or where further refinement could be needed to achieve a higher degree of desired simplicity. What feels simple today may not be tomorrow as the environment changes.

The pursuit of simplicity is an incremental journey characterized by imperceptible transformations and nuanced adjustments. It requires patience, fortitude to persevere in the process of change, acceptance of ambiguity, and faith in an iterative approach where progress may not be immediately discernible. While the ultimate destination may sometimes seem elusive, the journey itself is invaluable, as it refines both the solution and our comprehension of it. Regrettably, this process requires venturing beyond our cognitive comfort zone, compelling us to confront complexity directly and repeatedly testing and refining our designs and ideas, which can be profoundly mentally taxing. Nevertheless, when simplicity finally manifests, it bestows a distinctive clarity and resonance that renders the effort worthwhile.

Simplicity: Deceptively Simple

Simplicity transcends mere reduction; it unveils an underlying essence or purpose.

A sculptor cannot achieve simplicity by indiscriminately chipping away at a block of stone without a clear vision. Substantial and coherent results will not emerge. In essence, simplicity is a harmonious blend of subtraction and insight. The sculptor must possess a mental image of the desired form within the stone, guiding their actions with purpose and direction rather than randomness or relentless force.

In any endeavor to simplify—whether in design, writing, or strategy—a guiding vision or objective serves as a compass, informing the selection of elements to retain and those to eliminate. This vision prevents excessive reduction, resulting in an empty or disconnected state, and instead fosters the emergence of something essential and aesthetically pleasing.

The value of those who contribute to simplicity is often overlooked precisely because their work makes it appear effortless. Their efforts result in fewer visible complications, making the extent of their contribution easily overlooked. When these individuals depart, it reveals a hidden complexity that others may not possess the expertise to manage, demonstrating the depth of skill, intuition, and comprehension required.

Those who remain may struggle to manage what was previously smooth and intuitive, now encountering previously concealed complications. When a process or product functions seamlessly, it is easy to overlook the effort that went into achieving that state. Others may assume that what they observe is the natural state of affairs, unaware of the amount of effort invested in eliminating unnecessary elements and resolving potential conflicts. In many organizations, complexity tends to be more visible and, ironically, more rewarded. Individuals who are perceived as adept at managing complexities may be held in higher esteem than those who proactively prevent complexity from arising. Consequently, simplifiers can be undervalued until their absence reveals the magnitude of their impact.

We should create opportunities for those who simplify their processes and thinking to share them with the broader team. By doing so, we can help others understand and appreciate the thought and skill involved. This approach fosters an organizational culture that values and rewards simplicity. Additionally, it serves as a means of documenting and retaining tacit knowledge that can be challenging to capture.